Next: Resonance Up: Damped oscillations Previous: Underdamping:

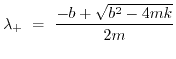

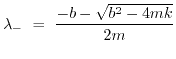

In this case both roots of lambda are real.

|

(1.75) | ||

|

(1.76) |

| (1.77) |

Here is an example of such a decay,

![]() .

.

Now as the damping ![]() increases, the two solutions

increases, the two solutions ![]() and

and ![]() become very different.

become very different.

![]() while

while

![]() .

When

.

When ![]() is very small, that means the decay is very slow. So as you

increase the friction

is very small, that means the decay is very slow. So as you

increase the friction ![]() , the decay is slowed down. This is the opposite that

happened in the above case of underdamping.

We call this case overdamping because there are no oscillations, but the

decay can be quite slow because the friction is so high that it's hard for

the mass to move.

, the decay is slowed down. This is the opposite that

happened in the above case of underdamping.

We call this case overdamping because there are no oscillations, but the

decay can be quite slow because the friction is so high that it's hard for

the mass to move.

So let's ask the following question. What is the best value of the friction

![]() to choose so that the mass comes back to equilibrium most quickly.

This is important if you were trying to design shock absorbers for a car.

If

to choose so that the mass comes back to equilibrium most quickly.

This is important if you were trying to design shock absorbers for a car.

If ![]() is too small it just oscillates back and forth for a long time

without decaying in amplitude much. If

is too small it just oscillates back and forth for a long time

without decaying in amplitude much. If ![]() is too large, like in molasses,

or tar, then it takes along time just to move the mass at all.

is too large, like in molasses,

or tar, then it takes along time just to move the mass at all.

It turns out, that the best choice of ![]() , is the critically damped case

where

, is the critically damped case

where ![]() . It is at the point straddling the over and underdamped

regimes. We won't solve this case but here is a plot of the way it looks

. It is at the point straddling the over and underdamped

regimes. We won't solve this case but here is a plot of the way it looks

This plots the function

![]() . The green line is a plot of

. The green line is a plot of ![]() .

.

josh 2010-01-05